The delta function was introduced by P.A.M. Dirac, one of the founders of quantum electrodynamics. The delta function belongs to the abstract concepts of function theory. In a rigorous sense it is a functional that picks a value of a given function at a given point. However, it also arises as the result of the differentiation of discontinuous functions. One of the most appealing properties of the delta function is the fact that it allows us to work with discretely and continuously distributed quantities in the same way, replacing discrete sums with integrals. Delta and its derivative meet the physical intuition in cases where we deal with quantities of large magnitude whose impact is limited to a small region of space or a very short amount of time (impulses). The inspiration for this particular article came during a course on mechanics in university.

In structural mechanics, it is often desired to understand the relationship between bending moment and shear force for objects, particularly beams, under applied loads. An explanation of the typical method is given here.

In the text I was using at the time, the proof of the relation between bending moment and shear force did not make explicit use of delta function. The final result was valid, but there was a serious fault in the proof. Point forces were considered as mere constant terms in the sum and differentiated away, despite the fact their contribution was accounted for only starting form certain points (suggesting delta-terms). I gave this problem a mathematically rigorous treatment which led to some nice closed formulae applicable to a very general distribution of load.

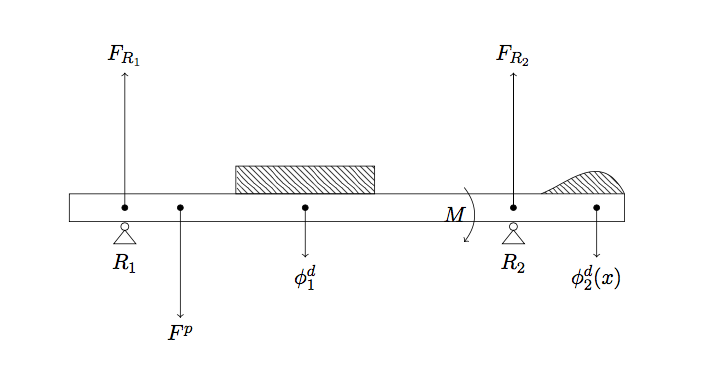

Consider a rigid horizontal beam of length $L$, and introduce a horizontal axis $x$ directed along it. Assume the following types of forces are applied:

Note that we ignore our own mass of the beam for the sake of clarity, although it can be easily accounted for if necessary.

Although the point forces $F^{p}_{i}$ are applied at certain points by definition, in reality the force is always applied to a certain finite area. In this case we can consider the density of the force being very large within this area and dropping to 0 outside it. Hence, it is convenient to define the distribution density as follows:

$$\phi^{p}_{i}(x)=F^{p}_{i}\delta(x-x_i).$$

Shear force $F$ at point $x$ is defined as the sum of all forces applied before that point (we are moving from the left end of the beam to the right one):

$$F=\sum_{x_i<x}F_{i}$$

Hence:

$$F^{p}(x)=\sum_{i}\int_0^x \phi^{p}_{i}(z)\mathrm{d}z=\sum_{i}F^{p}_{i}e(x-x_i),$$ where $e(x)=\begin{cases}1,\qquad x>0\\0, \qquad x\neq 0\end{cases}$ is the step function.

Now we shall find the contribution from the distributed forces. $\phi^{d}_j(x)$ may be formally defined on the whole axis, so we must cut off the unnecessary intervals outside $(a_j,b_j)$. Consider the following expressions:

$$\phi^{d}_{j}(x,a_j,b_j)=\phi^{d}_j(x)[e(x-a_j)-e(x-b_j)].$$

Indeed it is easy to ascertain that the right side is equal to $\phi^{d}_j(x)$ within $(a_j,b_j)$ and vanishes everywhere else. Calculating shear force due to distributed forces demonstrates some useful properties of the delta function:

$$\begin{aligned}F^d&=\sum_{j}\int_{0}^{x}\phi_{j}^{d}(z)[e(z-a_j)-e(z-b_j)]\mathrm{d}z\\&=\sum_{j}\left[\int_0^x\phi^{d}_j(z)e(z-a_j)\mathrm{d}z-\int_0^x \phi^{d}_j(z)e(z-b_j)\mathrm{d}z\right]\\&=\sum_{j}\left[\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_{j}(z)e(z-a_j)\mathrm{d}z-\int{b_j}^{x}\phi^{d}_j(z)e(z-b_j)\mathrm{d}z\right]\\&=\sum_{j}\left[\left.\left(e(z-a_j)\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right)\right|_{a_j}^x-\int_{a_j}^x\left(\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right)\delta(z-a_j)\mathrm{d}z\right.\\&\left.-\left.\left(e(z-b_j)\int_{b_j}^x\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right)\right|{b_j}^x+\int_{b_j}^x\left(\int_{b_j}^x\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right)\delta(z-b_j)\mathrm{d}z\right]\\&=\sum_{j}\left[e(x-a_j)\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z+e(x-b_j)\int_{x}^{b_j}\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right]\end{aligned}$$

Here we used the defining property of delta: $$f(x)\delta(x-x_0)=f(x_0)\delta(x-x_0),$$ from which it follows, in particular that $$\left(\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right)\delta(x-a_j)=\left(\int_{a_j}^{a_j}\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right)\delta(x-a_j)=0.$$

Now we shall calculate bending moments created by all types of forces involved. Consider $F^{p}_{i}$ applied at $x_i$. The bending moment created by this force evaluated at $x>x_i$ can be determined as follows:

$$\begin{aligned}M_{i}^{p}(x)&=F_{i}^{p}e(x-x_i)(x-x_i),\\M_{i}^{p}(x+\mathrm{d}x)&=F_{i}^{p}e(x+\mathrm{d}x-x_i)(x+\mathrm{d}x-x_i)=F^{p}_{i}e(x-x_i)(x-x_i+\mathrm{d}x),\\dM_{i}^{p}&=F_{i}^{p}e(x-x_i)\mathrm{d}x,\\M_{i}^{p}&=F_{i}^{p}\int_0^{x}e(z-x_i)\mathrm{d}z=F^{p}_{i}\frac{x-x_i+|x-x_i|}{2}.\end{aligned}$$ Hence, the total moment due to point forces is $$M^{p}=\sum_{i}F_{i}^{p}\frac{x-x_i+|x-x_i|}{2}.$$

To calculate moment created by the distributed forces we use the following approach adopted in mechanics. Replace the distributed force to the left of the point of summation with a point force applied at the center of gravity of the figure enclosed by the graph of $\phi_j(x)$ and lines $x=a_j$, $x=b_j$. If $a_j<x<b_j$: $$\begin{aligned}F^{d}_{j}(x)&=\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_{j}(z)\mathrm{d}z,\\ M^{d}_{j}&=\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}{j}(z)\mathrm{d}z\left(x-\frac{\int_{a_j}^x z\phi^{d}_{j}(z)\,\mathrm{d}z}{\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_{j}(z)\mathrm{d}z}\right)\\&=x\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_{j}(z)\mathrm{d}z-\int_{a_j}^x z\phi^{d}_{j}(z)\mathrm{d}z.\end{aligned}$$ Differentiating both parts with respect to $x$ we obtain $$\frac{\mathrm{d}M^{d}_{j}}{\mathrm{d}x}=\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_{j}(z)\mathrm{d}z+x\phi^{d}_{j}(x)-x\phi^{d}_{j}(x)=\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_{j}(z)\mathrm{d}z=F^{d}_{j}(x)$$

In fact, we could as well include point forces in the above derivation considering total density $\phi(x)=\phi^{p}(x)+\phi^{d}(x)$, which is the correct way to account for point forces in this proof. We can therefore derive the general relation between shear force and bending moment: $$F=\frac{\mathrm{d}M}{\mathrm{d}x}.$$ Now we need to calculate the contribution made by moments of pairs of forces. Each of these moments can be considered as a pair of equal large forces $F$ applied at a small distance $h$ of each other and oppositely directed. They will make the following contribution to the expression for total density $$\mu(x)=F\delta(x+h)-F\delta(x)=Fh\frac{\delta(x+h)-\delta(x)}{h}=M\frac{\delta(x+h)-\delta(x)}{h}.$$ Taking the limit as $h \to 0$: $$\mu(x)=M\delta'(x)$$

Note that the derivative of $\delta(x)$ is called the unit doublet.

This does not imply that expression for shear force will contain terms of the form $M\delta(x)$. This is due to the fact that shear force consists of vertical components of all forces and for pairs of forces those components will cancel out each other.

Therefore, the total bending moment of the pairs of forces is expressed as follows

$$M=\sum_{k}M_ke(x-x_k).$$ Finally we can write the expressions for shear force and bending moment in the most general case

$$\begin{aligned}F(x)&=\sum_{i}F^{p}_{i}e(x-x_i)\\&\qquad+\sum_{j}\left[e(x-a_j)\int_{a_j}^x\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z+e(x-b_j)\int_{x}^{b_j}\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right],\\M(x)&=\sum_{k}M_ke(x-x_k)+\sum_{i}F^{p}_{i}\frac{x-x_i+|x-x_i|}{2}\\&\qquad+\sum_{j}\int_0^x\left[e(t-a_j)\int_{a_j}^t \phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z+e(t-b_j)\int_{t}^{b_j}\phi^{d}_j(z)\mathrm{d}z\right]\mathrm{d}t.\end{aligned}$$

In an important particular case where $\phi^{d}_j(x)\equiv \phi^{d}_j$=const these expressions reduce to the following

$$\begin{aligned}F(x)&=\sum_{i}F^{p}_{i}e(x-x_i)+\sum_{j}\phi^{d}_j\left[(x-a_j)e(x-a_j)+(x-b_j)e(x-b_j)\right], \\ M(x)&=\sum_{k}M_ke(x-x_k)+\sum_{i}F^{p}_{i}\frac{x-x_i+|x-x_i|}{2}\\ &\qquad+\sum_{j}\frac{\phi^{d}_j}{2}\left[(x-a_j)^2e(x-a_j)+(x-b_j)^2e(x-b_j)\right].\end{aligned}$$

In this example we have demonstrated the application of Dirac delta and the related functions to a problem where the input data has a combination of continuous and discrete distributions. Singular functions allow us to work with this data in a uniform and relatively rigorous way. The advantage is that we get the final results in the closed form, as opposed to an algorithmic step-by-step method of solution. We can also obtain concise proofs, such as that for the relation between shear force and bending moment, and extend the results to very general inputs.